At the ELITE conference in Malang, Indonesia in September 2019 Dr Adrian Raper explained why a placement test must be adaptive. This is a summary of his talk.

Challenges

When you are designing a placement test, you are faced with a couple of challenges that you just don’t get with progress tests or proficiency tests. Firstly, you are limited by time. If you are running a progress test with your students, perhaps testing what you’ve taught that semester, it’s normal to spend an hour or more on it. For a high-stakes proficiency test like IELTS, three hours is considered to be acceptable.

But a placement test is perceived as low-stakes, and teachers, students and administrators are not prepared to invest so much time in it. My team and I have talked to a lot of stakeholders about this, and our research shows that the generally accepted limit is 30 minutes. So we have to be able to pinpoint the student’s level within a limited period of time.

The second challenge is that with a placement test, we have no idea of the student’s level of English. Almost by definition, you don’t know the students who are doing the placement test — that’s the reason they are doing it. So you might have one student who comes from a rural background, who has had very little exposure to English, and who is an A1. Sitting right next to them might be another student who spent part of their childhood in Australia and who is a C1 or even a C2. So a placement test has to cope with the whole spectrum.

Tests that don’t work

Let’s start by looking at the huge number of tests that simply don’t work. Go online and you’ll find literally dozens of free English tests. You’ve got, for example:

- The IH World Test

- Macmillan Straightforward Placement Test

- The St George English Test

- The Exam English Test

- And the British Council Online English Level Test

Typically, these tests have 100 multiple choice questions, and whatever the student’s level, they have to answer questions from A1 level all the way through to C2. They then get an averaged score at the end. At first sight, this doesn’t seem an unreasonable approach, so why doesn’t it work? Let’s take a look.

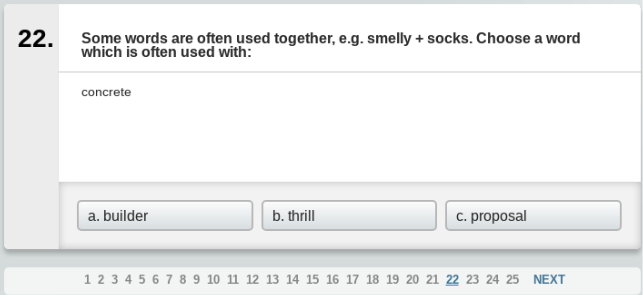

I went through the British Council test and got the first 20 questions wrong. So by now we should know that I am an A1 at best. But look at Question 22:

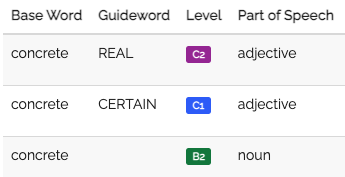

The question looks at collocations. Which word collocates with “concrete”? Vocab Profile tells us that “concrete” as an adjective is a C1/C2 word:

And of the three multiple choice options options, “thrill” is C1, “builder” is B1, and “proposal” is B2. So given that we now know for certain that I am no higher than an A1, why am I being shown this question so far into the test? It has no value, it is demoralising, and it is a waste of time. In fact this test perfectly illustrates the two problems we face with placement tests:

- If you have to ask questions at all levels, the test takes far too long.

- And because you have to ask questions at all levels, you can’t ask enough questions at the appropriate level. So you can’t fine-tune the student’s score.

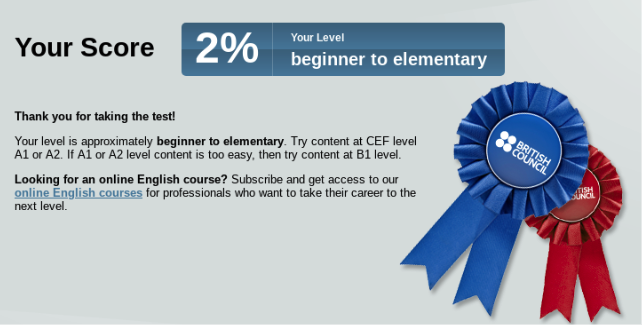

That’s why you come out with a result like this:

My British Council result (which looks very like a certificate) tells me I am A1 or A2 — or I might be B1. That covers half the entire CEFR scale. And I’ve only got 2%!

So we can see that this kind of linear, fixed test cannot work within the generally accepted time constraints, and also cannot cope with the range of levels that we need to cater to in a placement test. So what is the alternative model?

Adaptive tests

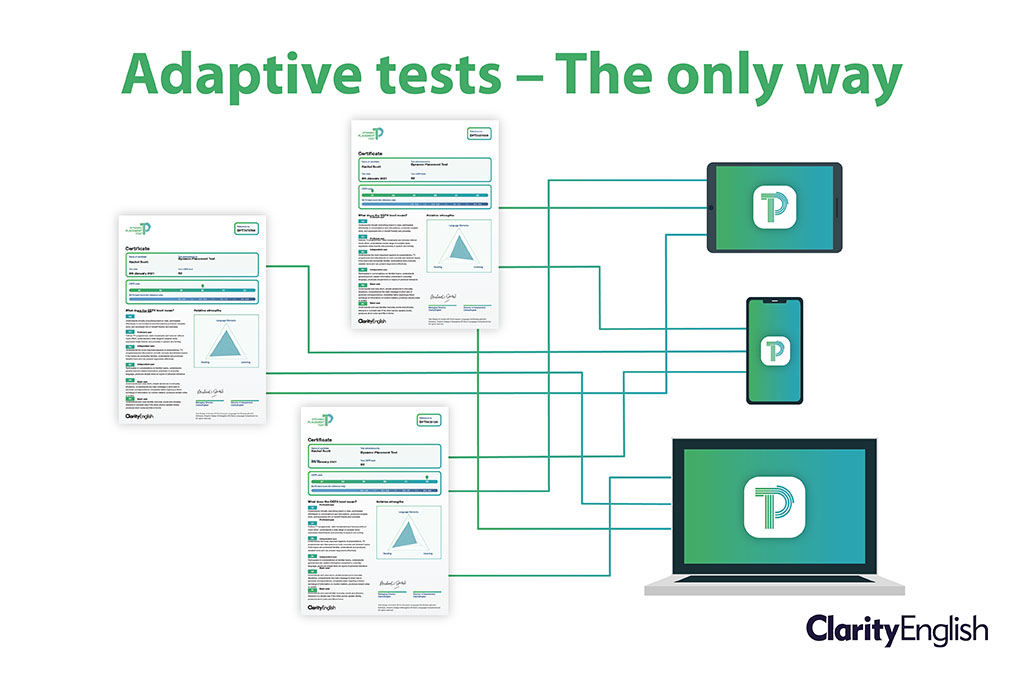

The solution, of course, is to use a computer adaptive test. First, let me define this term:

Adaptive tests are designed to adjust their level of difficulty — based on the responses provided — to match the knowledge and ability of a test taker. If a student gives a wrong answer, the computer follows up with an easier question; if the student answers correctly, the next question will be more difficult.

Definition from: edglossary.org

The interesting thing is that we’ve known for years that this kind of placement test needs to be adaptive. Let’s look briefly at a couple of research findings:

- “An adaptive test can typically be shortened by 50% and still maintain a higher level of precision than a fixed version.”

Weiss, D. J.; Kingsbury, G. G. (1984) - “Adaptive tests can provide uniformly precise scores for most test takers.”

Thissen, D., & Mislevy, R.J. (2000).

Over 20 years ago, Thissen and Mislevy, discussing item response theory, showed that adaptive tests are much better able to cope with a range of ability than fixed, linear tests. Fixed tests tend to be good for students in the middle range, but less accurate for those at either end — as we have seen with the British Council test that we looked at earlier.

OK then. The answer is that the test must be adaptive. What might an adaptive test look like?

Adaptive test structure

Let’s look at an overview of the structure that my team’s research and development project produced. This is the structure underlying the Dynamic Placement Test. There are two sections to the test: the gauge and the track.

- The gauge is the first part of the test. It aims to place a student within a broad level. In CEFR terms this is simply A, B or C. The gauge has between 10 and 20 questions that range from easy to difficult. Why between 10 and 20? Because if the student achieves a low score in the first 10, the test will not show them the more difficult questions in the way that the fixed test does.

- The second part of the test is the track. The gauge will put the test taker into the A, B or C track. Then when they are in that track, the questions will fine-tune and figure out the exact CEFR level — whether it is an A1 or an A2, or a B1 or a B2. And it will also tell us where in that level the student is, for example, high, middle or low B1.

What does this mean in terms of the two challenges we face? It means that the structure of the test is designed to maximise a test taker’s exposure to appropriate level questions. An A1 student will never see a C1 question. A C1 student will see a very small number of A1 questions as they climb quickly through the first part of the gauge and up to the C track. And because of this the adaptive model can reduce the time required to pinpoint the student’s level to 30 minutes. It is a very elegant solution.

Question types

There is another significant advantage to using adaptive tests that is not much commented on. A lot of publishers have simply taken their fixed paper-based test and computerised it. Typically, as we have seen, these are MC questions. But the additional time made available by using an adaptive rather than a fixed test means we can devise questions that require a deeper engagement with the language.

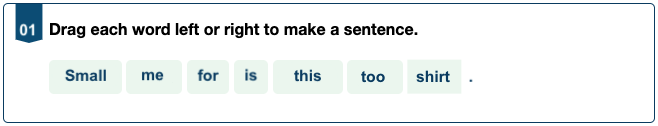

Here’s an interesting example:

First of all, answer the question. That’s easy. You’ve probably already done it. Then, as a linguist, as a language teacher, think about how you did it. How did you know which word belongs where?

You probably did it unconsciously, instinctively. But if we stop to think about it, our thought processes probably went a bit like this:

Noun + determiner (This + shirt)

Object pronoun (me) probably goes after “for”

If that’s the object, the shirt is probably the subject

Subject verb object — so where’s the verb — OK “is”

This shirt is… right, we’re probably looking for an adjective: “small”

“Too small”… “This shirt is too small for me.”

I’m not saying that test takers are consciously thinking in those terms: they’re not. But this is how their minds are working. They are interacting with the language in a very deep and complex way. This means that even in a test which is supposedly “receptive”, students are bringing their productive energy to the tasks. A test which is exclusively multiple choice is about as passive and boring as you can get; these question types allow test designers to go much further.

Conclusion

When my team and I started our test development project, I knew it would be much easier to make a fixed, linear test. So that is what we started working on. We wasted a whole year trying to make it work. And, for all the reasons given above, it failed.

The lesson we learned is that you need an adaptive test. And you need it for three reasons:

- To fit it into the time available — just 30 minutes

- To cope with the range of levels

- To be able to use complex, innovative item types

So to conclude, I’d like to leave you with a piece of advice. Don’t make the same mistake as I did and waste a year of your precious time. If you are designing a placement test, or if you are choosing an off-the-shelf placement test, make sure you go for an adaptive placement test. It is the only type that is accurate. It is the only type that works.

Further reading: